Timeline/Pictorial Memoir

“On Pilgrimage” was the apt title Dorothy gave her monthly column in The Catholic Worker newspaper. She was a naturally gifted documentarian, vividly capturing the dailiness of life around her and lifting out its meaning. She was also a memoirist, turning her reporter’s eye inward. For someone who treasured her privacy, Dorothy selflessly shared her state of mind and spirit, confiding her intimate thoughts, hopes, and struggles. Together with her diaries and letters, her writings form a rich spiritual trust.

Following is a timeline of her life, annotated at points by her writing and recollections. (Please note: for photographic credits, see the credits page. The Guild greatly appreciates the generous contributions of these artists and institutions).

Nov. 8, 1897. Born in Brooklyn, New York, into a nominally religious family described by one biographer as “solid, patriotic, and middle class”.

1906.

Experiences the San Francisco earthquake across the bay in Oakland. Her father was a sportswriter for a San Francisco paper.

The flames and cloud bank of smoke could be seen across the bay and all the next day the refugees poured over by ferry and boat….All the neighbors joined my mother in serving the homeless. Every stitch of available clothes was given away.

-

Aftermath of the San Francisco earthquake, 1906.

Family relocates to Chicago’s South Side. Her father was temporarily out of work but was later able to move the family to a comfortable house on the North Side.

At ten, interest in religion grows when her two brothers are enrolled in the choir of a Chicago Episcopal church. Studied the catechism and was baptized and confirmed.

Begins lifelong passion for literature. Reading at home was largely restricted to the classics, including the works of Dickens and Hugo. Discovers and begins to read on her own the social realist authors, Upton Sinclair and Jack London, as well as the writings of the communitarian anarchist, Peter Kropotkin.

I felt even at fifteen, that God meant man to be happy, that He meant to provide him with what he needed to maintain life in order to be happy, and that we did not need to have quite so much destitution and misery as I saw all around and read of in the daily press.

1913. Wins a scholarship to the University of Illinois. Begins to feel a growing disillusionment with religion, identifying its practice with those who are comfortable and well-off.

I wanted life and I wanted the abundant life. I wanted it for others too….and I did not have the slightest idea how to find it.

Entering the university a year later, joins the Socialist Party and the Scribblers Club, a college literary group. Not interested in traditional academic learning, she pursues her own reading, primarily in a radical social direction.

I had time to read, and the ugliness of life in a world which professed itself to be Christian appalled me….the Russian writers appealed to me too…. Both Dostoevski and Tolstoy made me cling to a faith in God, and yet I could not endure feeling an alien in it. I felt that my faith had nothing in common with that of Christians around me.

1916. Decides to follow her family back to New York, leaving the university and ending her formal education.

Secures work on socialist publication, The Call. After stating its opposition to American involvement in World War I, the latter is censored out of existence, and its male staff register for the draft.

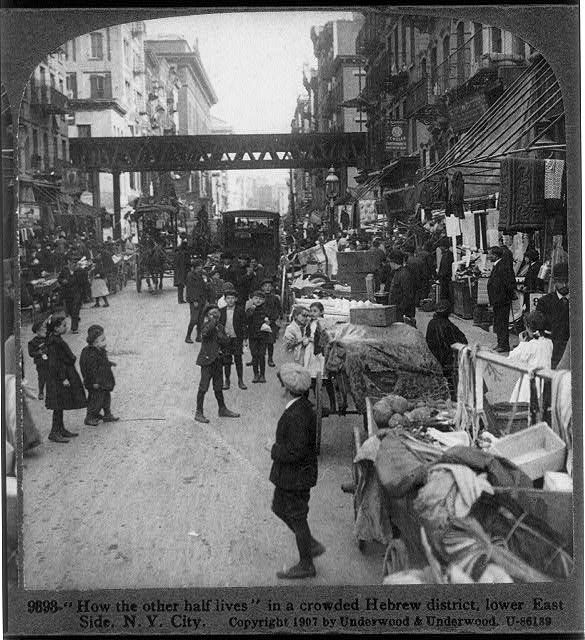

Rents a room from an Orthodox Jewish family on the Lower East Side. Recounts their kindness, even in their poverty, leaving food to greet her after late night print deadlines, complete with instructions on how to keep kosher.

-

Lower East Side, early 1900s.

1917. Takes her first bus trip as a “peace pilgrim,” part of an assembly of groups that were trying to arouse the public to oppose US entry into World War I. Accidentally clubbed by a policeman while covering an anti-war demonstration. Works briefly for the Columbia University branch of the Collegiate Militarism League.

Secures work with another Socialist publication,

The Masses.

Primarily because of a close friend’s involvement, accompanies suffragists from the National Woman’s Party to Washington to protest outside the White House. (Ironically, preferring direct action, Day never voted.) She is jailed and joins in a hunger strike. Scorns her own weakness in asking for a Bible for comfort. Released after 17 days.

1918. Works a short time for The Liberator, the successor to The Masses. Leaves it to do free-lance writing.

-

Suffragettes, Washington, D.C.

Begins to hang around Greenwich Village’s Provincetown Playhouse, where Eugene O’Neill was beginning to make his name as a playwright. After nights out, begins finding herself praying at St. Joseph’s Catholic Church.

I walked the streets with Gene….No one ever wanted to go to bed, and no one ever wished to be alone.

Many a morning after sitting all night in taverns or coming from balls at Webster Hall, I…knelt in the back of the church, not knowing what was going on at the altar, but warmed and comforted by the lights and silence, the keeling people and the atmosphere of worship.

At O’Neill’s urging, reads St. Augustine’s Confessions. “You have made our hearts for yourself, O God, and they will never rest until they rest in you.”

Spring 1918 – Early 1922. Seeing her writing as a meager response to war, signs on as a nurse trainee at Kings County Hospital, Brooklyn, where she attends to victims of the raging flu epidemic.

After a year, returns after a year to making her living as a writer. Later characterizes this period as a “time of drifting.” It includes infatuations and love affairs, one leading to an abortion in a failed effort to continue the relationship, and then to a rebound marriage of a year’s duration, spent largely abroad.

While in Europe, writes a thinly disguised autobiographical novel,

The Eleventh Virgin. Moves back to the States and to Chicago.

1923. Works as a reporter in New Orleans, at one point posing as a taxi dancer to write a first person account of the young women dependent on this way of life. (The generally male patrons of taxi dancing, highly popular in the 1920s and 1930s, would typically buy dance tickets for ten cents each, and the dancers, usually young women, earned a commission on every ticket they collected.)

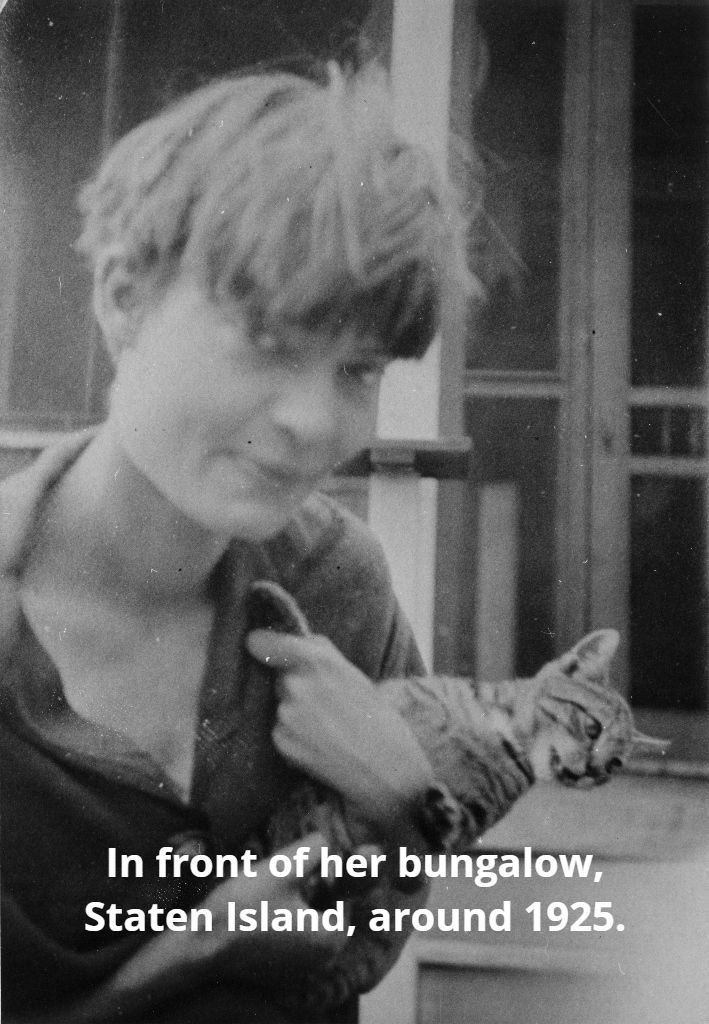

March 4, 1926.

Gives birth to a daughter, Tamar Teresa. Later, has the baby baptized, despite Forster’s objections.

December 28, 1927. Follows her daughter into the Church. Baptized at the Church of Our Lady, Help of Christians, in Tottenville, Staten Island, where she receives her first Holy Communion the next day.

I was all flustered with the occasion and I said to a woman, ‘Oh, I must get home. I’ve got a baby to feed. And the woman said, ‘Why, I didn’t know you were married.’ And I said, ‘I’m not.’ And you should have seen the expression on her face, wondering whether they hadn’t made a terrible mistake!

A friend of mine once said that it was the style to be Catholic in France, nowadays, but it was not the style to be one in America. It was the Irish of New England, the Italians, the Hungarians, the Lithuanians, the Poles, it was the great mass of the poor, the workers, who were the Catholics in this country and this fact in itself drew me to the Church

-

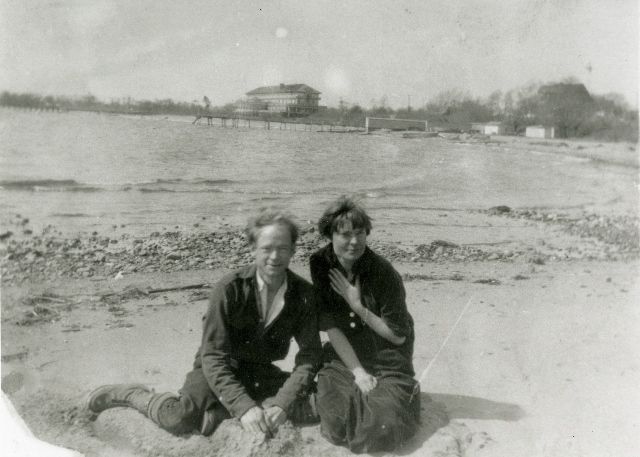

Day and Forster Batterham on the beach, Staten Island, around 1925.

1928 – 1930. Separates from Forster, mourning their differences, at times trying to minimize them, but finally unable to reconcile them. A time of wandering ensues, with stints in Hollywood as a scriptwriter, and in Mexico City, supporting herself and Tamar through her writing.

-

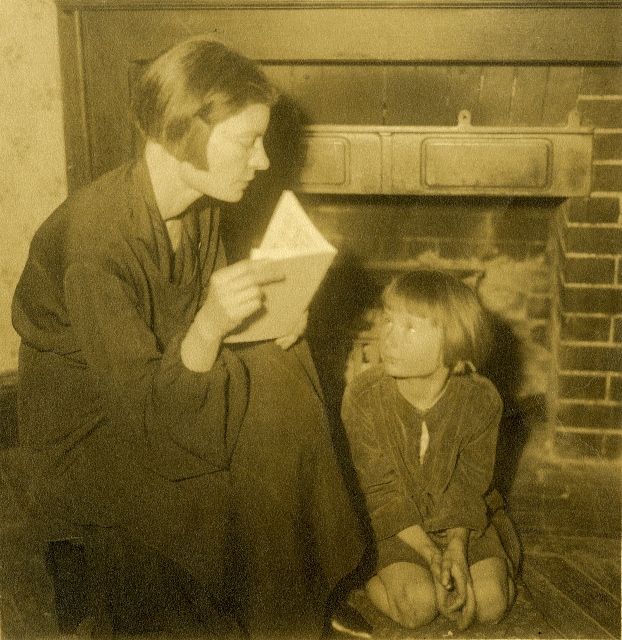

Day reading to Tamar, around 1932.

December 1932. Travels to Washington, D.C. to cover the “Hunger March of the Unemployed,” a communist-organized demonstration, for the Jesuit journal America and for The Commonweal, a liberal Catholic magazine. Prays at the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception on December 8 that she might find a way to combine her Catholic faith and her commitment to social justice.

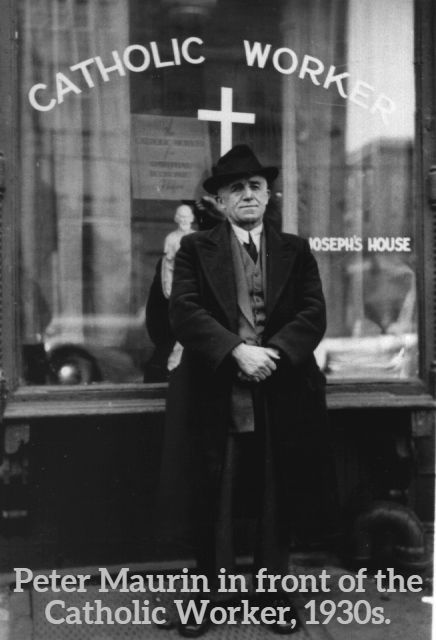

Upon her return to New York, meets Peter Maurin, a worker and a scholar imbued with Catholic social thought and teaching.

-

Stiking Auto workers, Flint, Michigan, 1937

-

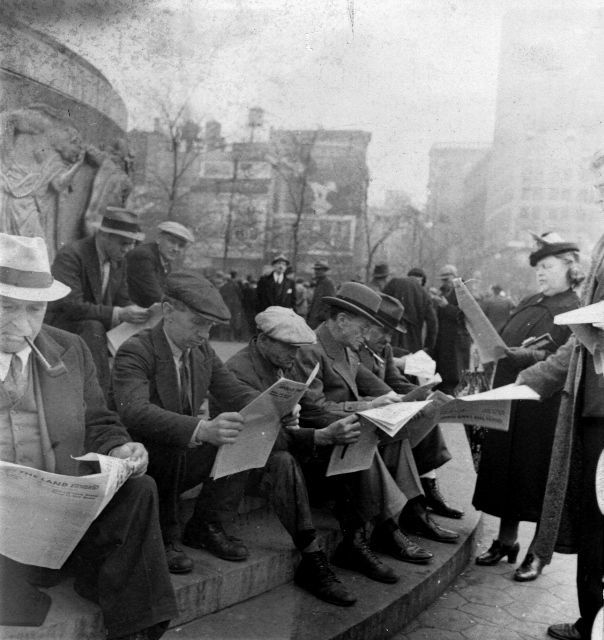

Catholic Worker

readers, Union Square, New York City, c.1940.

1940.

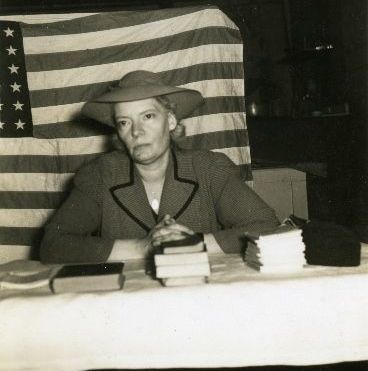

First retreat at Maryfarm. In July, testifies before Senate Military Affairs Committee on conscription. Draft registration begins in October.

-

Dorothy Day speaking, 1940, Seattle, Washington.

What we would like to do is change the world — make it a little simpler for people to feed, clothe, and shelter themselves as God intended them to do. And to a certain extent, by fighting for better conditions, by crying out unceasingly for the rights of the workers, of the poor, of the destitute…we can to a certain extent change the world…. We can throw our pebble in the pond and be confident that its ever-widening circle will reach around the world.

We repeat, there is nothing that we can do but love, and dear God — please enlarge our hearts to love each other, to love our neighbor, to love our enemy as well as our friend.

1949. Catholic Worker supports the cause of cemetery workers on strike against the Archdiocese of New York.

May 15. Peter Maurin dies at Newburgh. In a suit sent in for the poor, he is buried in a donated plot in St. John’s Cemetery, Queens, following an exultant Requiem mass.

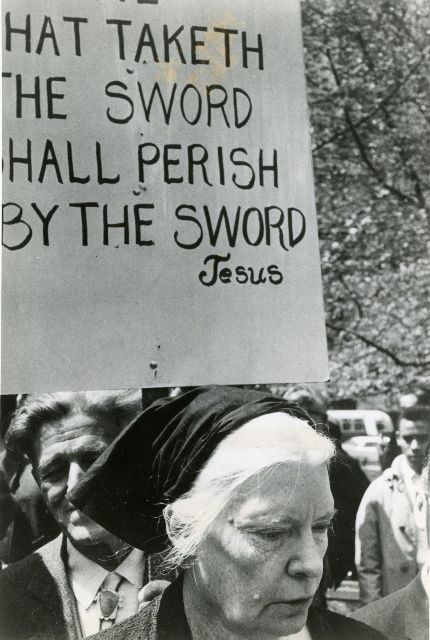

1950. Travels to Washington for a one-week fast for peace. Protests the stockpiling of nuclear weapons, a cause she would champion the rest of her life.

In the Psalms…we ask to be freed from the fear of the enemy, not the enemy, but from the fear.”

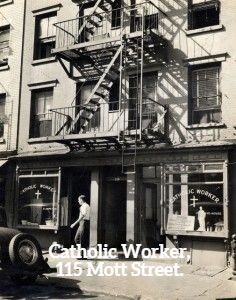

Move to new Peter Maurin Farm on Staten Island. Catholic Worker moves from Mott Street to 221 Chrystie Street.

1952. Publication of autobiography, The Long Loneliness. Speaks at Carnegie Hall in a meeting against the Smith Act.

1954. Anticipates US military involvement in Vietnam and questions wars to protect American standard of living.

1955. Arrested for refusing to participate in mandatory civil defense drills. First of annual protests until the drills in 1961 are cancelled; spends a total of 45 days in jail.

1957. Travels to Georgia to support the interracial Koinonia community. Shot at while taking a turn as sentry.

1958. Forced to give up Chrystie Street house, Catholic Worker community disperses to apartments. Rents store-front at 39 Spring Street for office and soup kitchen.

-

At civil defense drill protest, c1960.

1961. Catholic Workers participate in sit-in at the Atomic Energy Commission building in New York City.

1963. Travels on peace pilgrimage to Rome. Sees Pope John XXIII in a public appearance at the Vatican. Publication of Loaves and Fishes.

1964. New Catholic Worker farm at Tivoli, New York. Catholic Worker joins other peace groups in sponsoring protests against the Vietnam War.

1965. Sails to Rome for the final session of the Second Vatican Council. Takes part in a ten-day fast by an international group of women to encourage the Council to make a clear statement on war and peace. Later heartened when the Council publishes

The Church in the Modern World

which condemns indiscriminate warfare and supports conscientious objection.

Five young men burn draft cards in Union Square. Joins with another aging veteran of the peace movement, A.J. Muste, to speak and lend support.

1967. Travels to Rome for the International Congress of the Laity. One of two Americans invited to receive Communion from Pope Paul VI.

1968. Catholic Worker moves to St. Joseph House, 36 East First Street.

Paper work, cleaning the house, dealing with the innumerable visitors who come all through the day, answering the phone, keeping patience and acting intelligently, which is to find some meaning in all that happens — these things, too, are the works of peace, and often seem like a very little way.

1969.

Visits the headquarters of the United Farm Workers in Delano, California. While picketing with farm workers, has to jump to avoid a speeding car swerving in her direction.

-

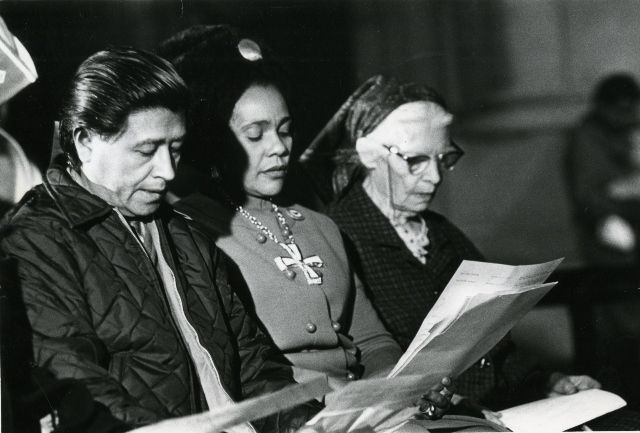

With Cesar Chavez and Coretta Scott King, Cathedral of St. John the Divine, NYC, 1973.

1972.

Marking her 75th birthday, the University of Notre Dame awards her the Laetare Medal for “comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable.”

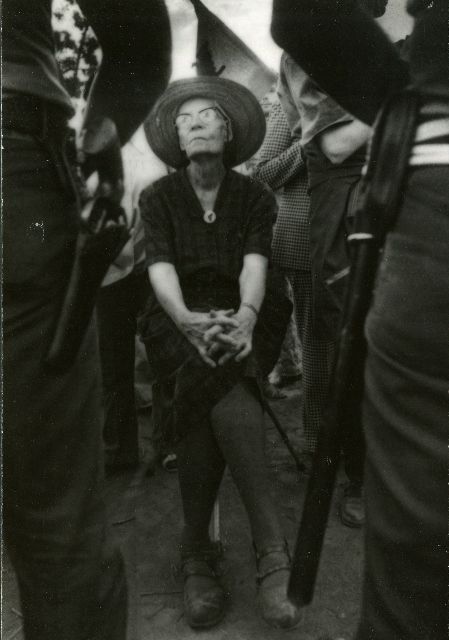

1973. Joins Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers in California’s San Joaquin Valley to organize field workers. Arrested and spends nearly two weeks in a prison farm.

I was glad I had my folding chair-cane so I could rest occasionally during picketing, and sit there before the police to talk to them.

-

Picketing with the United Farm Workers.

1974. Catholic Worker purchases a former music school at 55 East Third Street. Intended as a shelter for homeless women, it takes the name of Maryhouse.

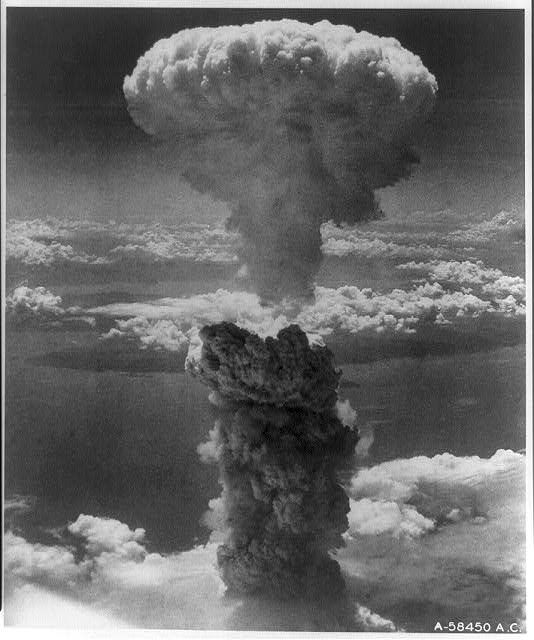

1976. Addresses the Eucharistic Congress in Philadelphia on the Feast of the Transfiguration (Hiroshima day). Soon after, suffers a heart attack.

1977. Receives a personal greeting from Pope Paul VI on occasion of her 80th birthday.

1978 Awarded first “Teachers of Peace” award by Pax Christi USA, part of the international Catholic peace movement.

1979. Catholic Worker closes farm in Tivoli. Opens Peter Maurin Farm in Marlboro, New York.

-

A Communion of Saints: Dorothy Day and Mother Teresa

June. Meets for a last time with Mother Teresa.

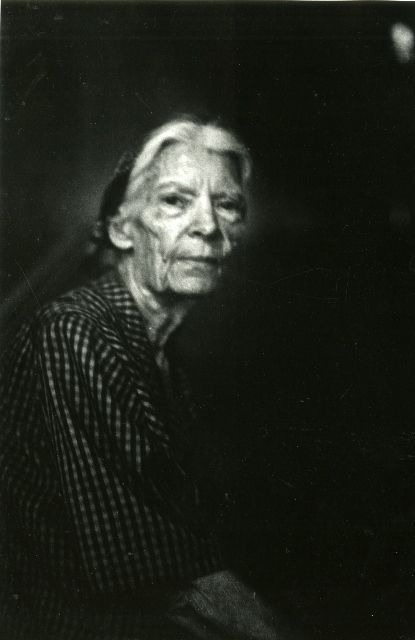

-

Dorothy Day at Maryhouse, 1979.

November 29, 1980.

Dorothy Day dies at Maryhouse in New York.

If I have accomplished anything in my life, it is because I wasn’t embarrassed to talk about God.

1980. Memorial Mass celebrated at St. Patrick’s Cathedral. A hush falls over the throngs of people when Cardinal Terence Cooke, while acknowledging that he did not always agree with Day, states simply that “we may have had a saint in our midst.”

-

Day’s Funeral Procession, New York, NY.

2000. Cardinal John O’Connor of New York initiates the cause of her sainthood. The Vatican approves the cause and grants the title “Servant of God.”

2005. The Dorothy Day Guild is established to promote her life and works.

2012. U.S. Bishops unanimously vote to endorse the sainthood cause of Dorothy Day at their fall general assembly in Baltimore, Maryland.