PHONE

555-555-5555

ADDRESS

Dorothy Day Guild

1011 First Avenue, Room 787

New York, NY 10022

About Dorothy Day

Slide title

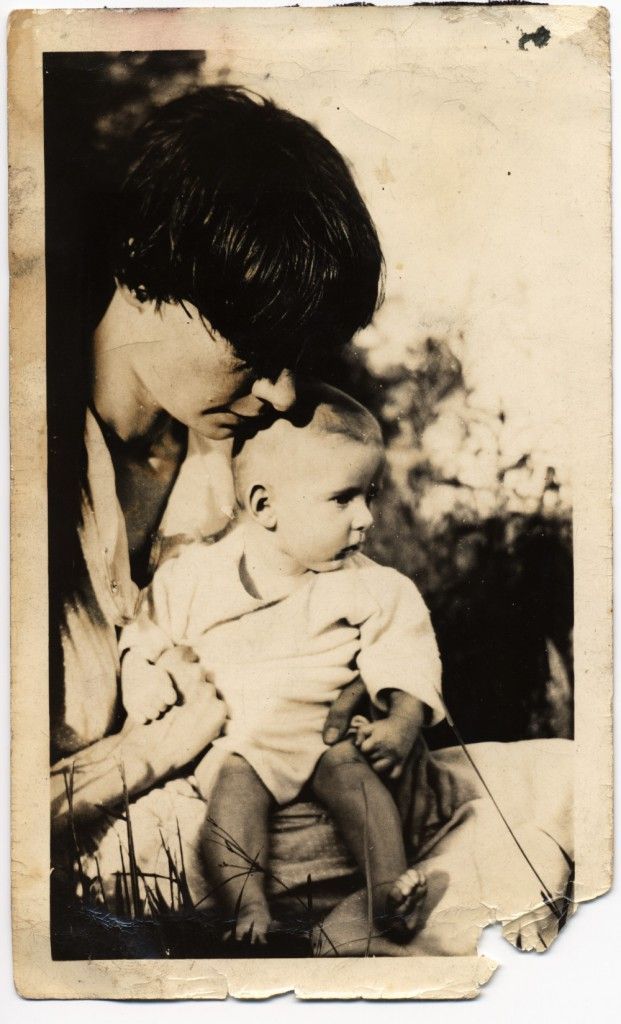

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

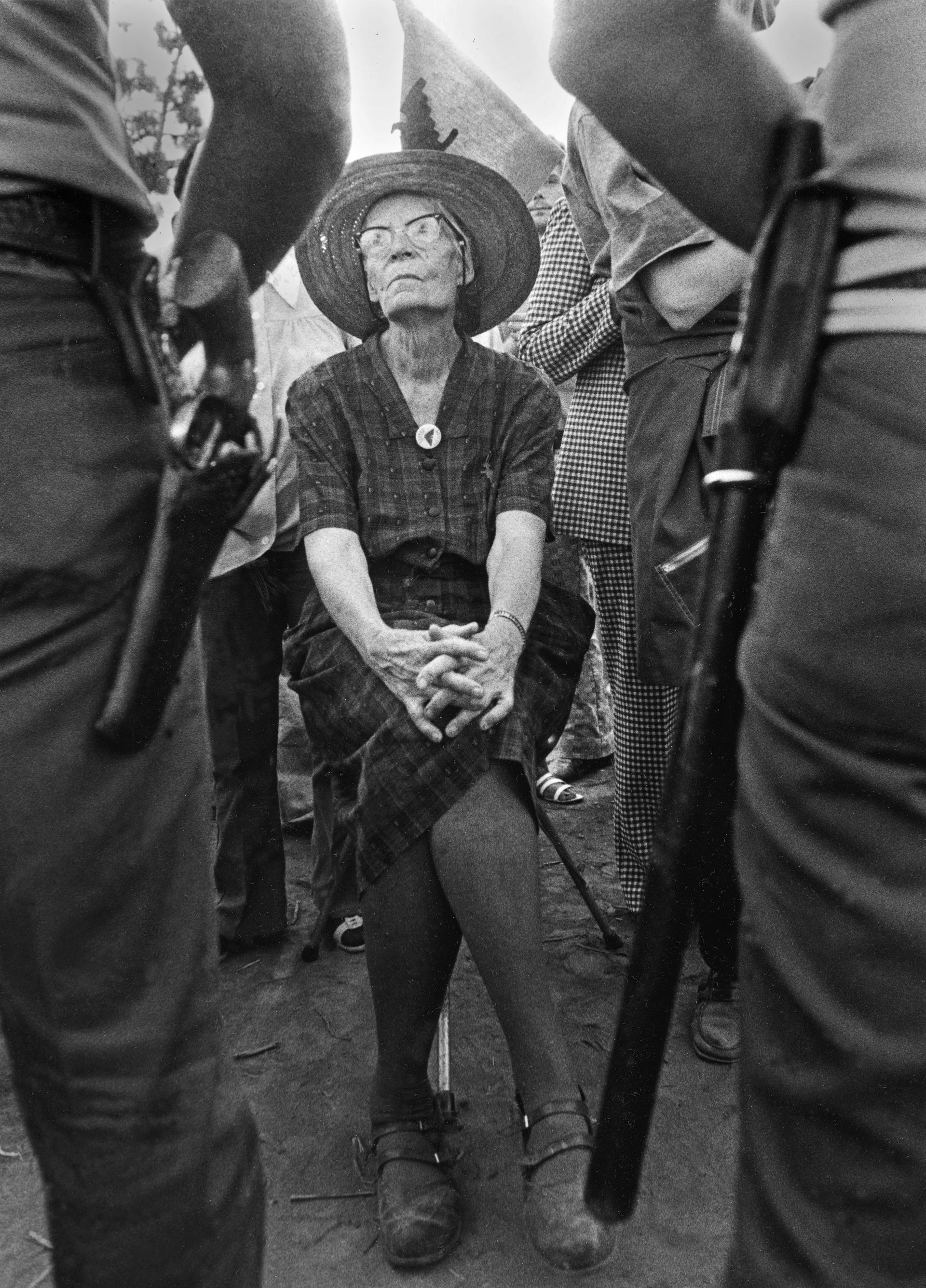

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Born in Brooklyn, New York, on November 8, 1897, Dorothy Day grew up in the San Francisco Bay area and Chicago. Her early life was marked by a passion for writing and an acute sense of social justice. She began studies at the University of Illinois, but left to pursue her dreams as a writer.

In New York City, Day worked as a journalist on socialist newspapers, participated in protest movements, and developed friendships with artists and writers. She also went through failed love affairs, a suicide attempt, and an abortion, experiences she drew upon in writing a novel.

During those bohemian years, the young Day came face to face with an emptiness, a loneliness that she later recognized as a longing for God. When Hollywood producers purchased the rights to Day’s novel, she bought a small seaside cottage on Staten Island. There, she lived happily with her partner, Forster Batterham. However, Batterham rejected both marriage and religion while Day grew increasingly attracted to the Catholic Church as the “Church of the poor.”

When she gave birth to a daughter in 1926, in her great joy, Day turned to God in gratitude. Her faith took root. As she later described in her spiritual autobiography, The Long Loneliness, her decision to have her daughter Tamar baptized and then to enter the Church herself led to the end of her common law marriage.

At first, Day struggled to find her place as a Catholic. While covering the 1932 Hunger March in Washington, D.C., at age 35, she lamented the absence of the Church — which, she felt, should have been at the forefront of the march. At the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, she wrote later, “I offered up a special prayer, a prayer which came with tears and anguish, that some way would open up for me to use what talents I possessed for my fellow workers, for the poor.” The next day, she met Peter Maurin, a French immigrant and former De La Salle Christian Brother. Maurin introduced her to the Church’s social teaching and to his own vision for “a new society within the shell of the old.”

On May 1, 1933, during the depths of the Great Depression, Maurin and Day launched the Catholic Worker newspaper. Within only a few years, the paper’s circulation soared and dozens of Catholic Worker houses sprang up across the country. The movement’s members embraced a simple lifestyle (“voluntary poverty”) and cared for poor and homeless people.

The Catholic Worker Movement was also shaped by Day’s unwavering commitment to pacifism. She wrote scathingly about the devastation wrought by atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki and protested against nuclear weapons. She joined in nonviolent actions with the civil rights movement, the anti-Vietnam War movement and the United Farm Workers. All the while, over the following decades, she wrote, traveled, gave talks, and encouraged people to practice the Works of Mercy.

Day’s pilgrimage ended on November 29, 1980 at Maryhouse, a Catholic Worker house for unhoused women in New York City. After her death, historian David O’Brien called her “the most important, interesting, and influential figure in the history of American Catholicism.”

A Woman of Conscience, a Saint for Our Time

The Dorothy Day Guild supports and advances the cause for canonization of Dorothy Day, initiated by the Archdiocese of New York as a saint by the Roman Catholic Church, and promotes, for the benefit of all people interested in social justice, awareness of Dorothy Day, her writings, the Catholic Worker Movement she co-founded, and her life and witness to the Gospel.

QUICK LINKS

© 2023 All Rights Reserved | Dorothy Day Guild | This site is powered by Neon One