Blessed are the peacemakers. With deep sadness, the Guild mourns the loss of longtime Catholic Worker, Tom Cornell, who died peacefully early this morning. We also rejoice in his life! As a young man, Tom embraced the Catholic Worker vocation in its totality: from peacemaking to hospitality. He met his wife, Monica, at the CW in NYC in the 1950s. Theirs was a most faithful witness. In recent years it led to the running of Peter Maurin farm in Marlboro, New York. Not only did they embody the CW tradition, they passed it on to their children, Deirdre and Tommy, and nurtured it in countless others.

Tom and Tommy reflected on the continuing influence of Dorothy Day on their lives and family in the following piece, originally written two years ago for the Guild’s newsletter which Tom helped edit. Tom recalls how shortly after his first visiting the Worker, he became “part of the woodwork.” Though always a little loathe to challenge Tom’s fierce intelligence and forceful presence, we dare this correction. Tom became — and will always remain — part of its living roots. Deo Gratias.

BREAKING BREAD

by

Tom Cornell and T. Christopher Cornell

(This multi-generational reflection first appeared in the “Breaking Bread” column of the Summer/Fall 2020 issue of the Guild’s newsletter, In Our Time.

)

OUR CATHOLIC WORKER FAMILY

My very first trips to the New York Catholic Worker were to attend Friday Night Meetings for the Clarification of Thought. One night, Dorothy sat knitting while listening. I don’t remember the topic, or the speaker, but after the presentation, her silence ended: “Security! I don’t want to hear about security. There are great things that need to be done, and who will do them but the young? And how will they do them if they’re worried about security?” These – the first words I heard Dorothy Day speak – lifted me out of the trajectory I had previously set for myself. Those words, and Dorothy’s radical witness, led me to another path, which in turn led me to Monica, and the life we would lead together.

Monica’s parents, George Ribar and Carlotta Durkin Ribar, had helped to establish the Catholic Worker in Cleveland, during the late 1930s. Monica’s aunt, for whom she was named, Monica Durkin, was a friend of Dorothy Day and a member of Friendship House in Harlem. When Dorothy’s classic memoir, The Long Loneliness,

was published in 1952, Monica’s parents got a copy from the library. Though they read The Catholic Worker

and sent modest donations to the Worker in New York City, they did not warm to Dorothy’s criticism of the social/economic/ political system, “this filthy rotten system.” Their interest was in the Works of Mercy, and they practiced them, taking in the four children of a relative. Monica’s sister, Carlotta, spent a few months at the Catholic Worker in New York City in 1961-62,and she encouraged Monica to give it a try since Monica felt she “wasn’t doing anything” at college in Cincinnati.

I had been managing editor of The Catholic Worker

for a year at the time and had been away at my mother’s home in Connecticut the day of Birmingham Sunday (when four little black girls were killed when their church was fire-bombed). When I arrived back at the CW, a dilapidated storefront at 175 Chrystie Street (the ground floor was the soup kitchen; the second floor, a day room; and the third floor, the business and editorial office), I intended to go straight upstairs to my desk when someone grabbed my arm and said, “You have to meet the new girl!” Bless his heart, I did! Monica was doling out soup at the far end of the room. She was tall, and those brown eyes! I learned which Mass she would be attending the next Sunday and made sure to sit beside her. After Mass, we went to the nearby Café Roma for cappuccino and pastry. We were married seven months later and after fifty-six years of marriage have seven descendants.

Nothing in my family background would have oriented me to the Catholic Worker Movement. My father died when I was fourteen – but had he lived, he would have disowned me. I have seventeen first cousins, all on my mother’s side. Most of them were scandalized at my doings during the Viet Nam War. I was uncomfortably visible, on the front page of The New York Times

and several other major newspapers, burning my draft card. While I was doing my time, serving six months in prison, the New York Times

Magazine commissioned me to write an article on that experience. It was printed to some notice, none of which soothed my relatives.

The New England Province of the Society of Jesus, the Jesuits, prepared me to meet and to follow Dorothy Day. I spent eight years at Fairfield Prep and Fairfield University in Connecticut (1948-56). The Jesuits were, and are, very strong on spiritual development, and as a result, I wanted to be as authentic a Christian as I could. As rich as the experience at Fairfield was, I sensed there was something missing, and that was social engagement. In fact, such involvement was considered a danger to spiritual health. When I came upon Dorothy Day’s The Long Loneliness

, I felt that this is what I was looking for. It wasn’t long before I was hooked, visited the CW headquarters,and soon became part of the woodwork.

I knew that I wanted to marry and to raise my own family. I earned a Master’s degree as a teacher. I could support a family! I could look for a bride! And where else but at the Catholic Worker? How Monica and I practiced the aims and means of the CW as a married couple and then as a family of four, a boy and a girl, is the purpose of this writing.

Before all else, it’s hospitality. Our first apartment was three small rooms within a short walk to the CW. The rent was $65 a month, and I could make that with two days substitute teaching. After the regular CW Friday night meetings, about fifteen people jammed into that little apartment for continuing discussion and beer. When our second child was born, we moved to a bigger apartment, again within walking distance of the CW and the office of the Catholic Peace Fellowship (CPF), where I worked. We had an unexpected addition to the family when Monica’s mother called to inform us that the mother of the four children she had taken in had died, leaving another, a four-year-old boy. Monica and I raised him as our foster-child until he was eight. So, from early on Tommy and Deirdre shared their living space, their lives.

Next, we moved to a six-room apartment in Brooklyn, the rent $110 a month, a steal even then! A young friend, who also worked for the CPF, moved in with us and lived and ate with us. It worked very well, and he was a great help with the children

When we later moved to Newburgh, New York, to an aging but beautiful house on the Hudson River, a young neighbor gathered his buddies on our front porch to play cards. When the weather turned cold, we invited them in. One of those boys is living with us on the farm today.

I don’t think Tommy or Deirdre ever sat down and pondered the “Aims and Means of the Catholic Worker.” I don’t think they ever decided to be Catholic Workers. They simply came to the realization that that’s what they are. When Monica and I moved the family to Connecticut so I could take a job as a soup-kitchen director, Tommy ran a second soup kitchen under my direction. He knew how to be with people, even hurtful people, who are hard to deal with! We lived in a twenty-three-room former convent, renamed Our Lady of Guadalupe House of Hospitality. After college, Deirdre volunteered for a year in Mexico. There she met Kenney Gould, from the Los Angeles Catholic Worker, and they married. They later went on assignment to Oaxaca, Mexico, as lay missioners with Maryknoll. They left with three children and came back with five. Here in New York State, only a few miles from us, Deirdre and Kenney became deeply involved with Reaping the Harvest, a Catholic accompaniment project for farm workers. They became so enmeshed in the community that they have over thirty godchildren.

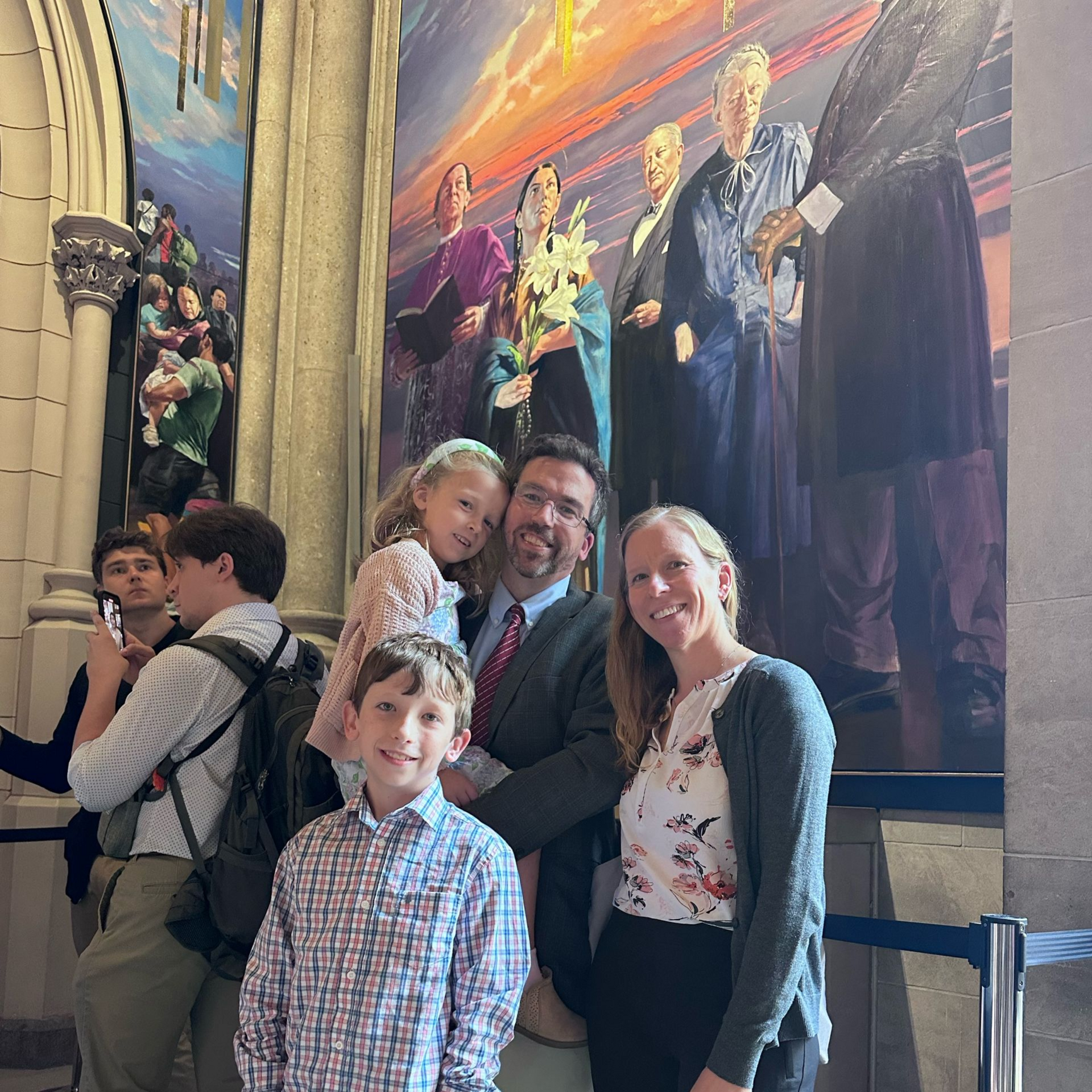

Tommy is our chief gardener at the Peter Maurin Farm, and he writes for the paper under the name T. Christopher Cornell. A Catholic Worker family? Q.ED.!

By T. Christopher Cornell

As an adult, I never “knew” Dorothy Day. But I’ve spent my lifetime dealing with her indirectly—in the third person. Yes, I met Dorothy many times as a child; our family spent a summer at the Tivoli farm, and we made multiple trips to the Worker in New York City. However, Deirdre and I were “just kids,” and there is a famous story that, to “kids,” Dorothy was “just an old lady.” Dorothy’s impact on Deirdre and me would show up later and came mostly from those around Dorothy.

My parents created their own hybrid form of a Catholic Worker family life. They met and married at the Catholic Worker in New York City and by the time I was in second grade, we left New York for a smaller city, and my father had an office job in the peace movement. They used his salary to buy a rambling house, a fixer-upper, in an integrating neighborhood. My sister and I received a Catholic education from the parochial school and a full dose of neighborhood life. But we were always different from the other kids. We had hand-me-down clothes and counted out our milk money. The peace movement was a mystery to our neighbors, most of whom had been in the military. Personal nonviolence and civil-rights issues were in genuine concern at our home. We always had a Christ room, for a guest, and we had a constant flow of visitors,whether a political prisoner from Argentina or a student from Barcelona. I really can’t remember a time that we didn’t have at least one person living with us. All the while, my parents also had an informal salon that included a mixture of my father’s rough-and-tumble working-class buddies from the neighborhood and Catholic Worker movement types. That left me with a permanent craving for the intellectual and religious foment typical of the era.

High school years found us in yet another decaying, post-industrial city. During those years, my parents started another hybrid Catholic Worker community. They ran a soup kitchen funded by an ecumenical agency and used the salary to support a house of hospitality, 24/7, for a blended community of family, soup-kitchen guests, and workers. It was there that my sister and I experienced the joys of community life. Though it was short-lived, this experience was defining. Most of all, there was the work: feeding people; seeing Christ in the stranger; the works of mercy, daily, repeated. There is no need to enumerate the love, grief, and the communion that happens with people in such circumstances. The stories are universal.

More than thirty years later, my sister and I are still being shaped by Dorothy’s impact on forming our family. We have inherited a legacy which, over time, reveals Dorothy’s lasting influence. My sister is a busy mom and involved in pastoral projects with immigrants and farm workers. My parents and I live in a community of twelve at the Catholic Worker farm in Marlboro, New York.

Although both of my parents worked directly with Dorothy at a time when she was still in her full vigor—mentally and spiritually—they were not her contemporaries. They were a generation removed, and, unlike Dorothy, were not converts. They were members of the postwar immigrant Church when it was still separate from the dominant U.S.culture, but was beginning to assimilate. My mother’s formation followed the pipeline of parochial school, Catholic high school, Catholic women’s college, and the convent. My father came from eight years of Jesuit education. Even now, both carry something of that intense, Pius XII-era devotional Catholicism. The Catholic Worker gave them a locus for their religious energies in the time of aggiornamento. A quote from my mother may illustrate what I mean. During a panel discussion, my mother was asked how she maintains tolerance for the institutional Church’s deeply imbedded hierarchical structure. She shrugged it off by saying “Oh, I don’t worry about it, we have the saints.” At the time, I was unnerved by the comment, thinking it was a refusal to engage in the much-needed work of faithful dissent that would move the Church forward. Now, I see it instead as an embrace of her identity in the lay apostolate, bringing the strength of the immigrant Church’s sensibilities and the sensus fidelium

to bear on her life’s vocation, no matter the condition of the institution around her.

I asked my mother recently if it would be fair to say that Dorothy influenced everything she ever did after meeting her. “Yes,” she said, quickly and emphatically. The force of Dorothy’s personality and the way it registered with people is attested to very well, yet it is hard to describe the nature of these relationships accurately. They certainly formed my parents, and indirectly, me and my sister.

As an adult, living and working as a Catholic Worker, I have developed my own relationship to Dorothy, through my own experiences in the movement, and importantly, through reading her writing. I find her writing to be uniquely incisive and moving. Conversations and testimonies about her, even now, continue to help me understand better how a person like Dorothy—with such authenticity—left others a permanent conviction to live their own lives differently. Even those who “came to her” after her death have been convinced by it. The power of her witness is strong enough to carry over generations.