Anne Klejment

:

Dorothy’s opposition to World War I reflected the antiwar influence of the Left and Progressive reformers. Initially, she hoped that working people would not support war, that they would view it as a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight. She was quickly disabused of her expectation. As a reporter for the Socialist Call

, she was sent to Washington, D.C. by bus to cover an antiwar protest of progressives and radicals that attempted to prevent U.S. entry into the war. Along the route, she discovered that ordinary folks were not sympathetic to the protesters. Later she admitted that her stories depicting antiwar crowds were false: “Most of it [the swell of antiwar support while headed to D.C.] was imaginative.”

Antiwar reformers and radicals were troubled that banking and industrial interests would gain considerably from war profiteering. Workers would be risking their lives and livelihoods to advance the interests of the wealthy. Radicals aimed to eliminate capitalism. Reformers preferred to curb its excesses. And both viewed the idea of the war as repugnant. Some Progressives contended that conflicts should be ended by civilized means, not by violence. And radicals, desiring to advance the solidarity of the working class, were repelled by workers from different nations killing each other. They dreamed of a world in which the class interests of workers would prevail over those of the wealthy few.

During World War I, the term “pacifism” was fluid in meaning. Anyone who opposed the war for any reason could be labeled a pacifist, even if they advocated violence in other situations. Dorothy was antiwar, but not a pacifist as we understand it today, meaning as an opponent of all wars and violence. As she later explained, “I was pacifist in my views—pacifist in what I considered an imperialist war though not pacifist as a revolutionist.” At the time, she still supported the revolutionary violence of the common people and the political vanguard during the Russian revolution.

To raise an army, the Wilson Administration resorted to compulsory military service through the draft. It would be unsuccessfully challenged in the Supreme Court on the grounds that military conscription was a form of slavery and therefore contrary to the Thirteenth Amendment. That argument, of course, failed.

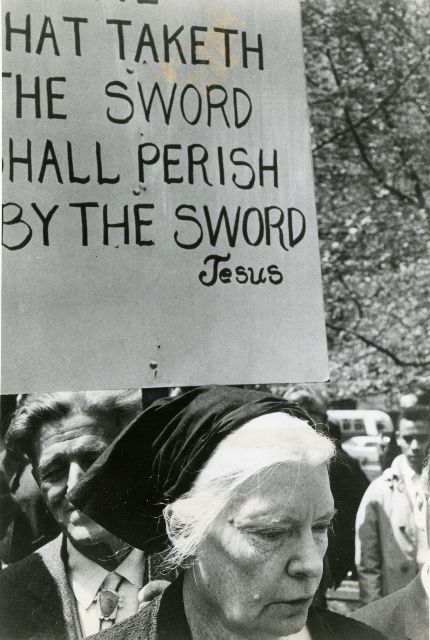

Dorothy Day, pictured between other young reporters for the Socialist paper, ‘The Call,’ protesting the United States’ entry into World War I.

Dorothy was close to men who were facing this highly charged personal and political decision. Some opposed the draft. Most registered, a few did not. She wrote compassionately about their anguish. Some found themselves in legal jeopardy, either spending time in jail or heading to Mexico to evade registration, induction, and imprisonment.

Dorothy carefully wrote about these friends in The Long Loneliness

, which was published during the Cold War. She even changed someone’s name to protect a person charged but found innocent. In a related case, she mentioned an alias of another person without connecting it to his identity. It’s important to know that she did this during the height of the McCarthy anticommunism scare! She refused to risk subjecting them to further government scrutiny—even decades later. Others were ratting on alleged subversives, but she refused to stoop so low.

The wartime suppression of freedom of speech and freedom of the press deeply concerned Dorothy as did the imprisonment of World War I opponents. Remember, government suppression of freedom of expression ended her employment with The Masses

in the fall of 1917. She was unemployed when she joined the women’s suffrage protests as a “Silent Sentinel.”

Dorothy understood that war resisters were political prisoners, whereas most average Americans considered resisters to be unpatriotic, even traitorous. The militant suffragists were political prisoners, too. This is one of the reasons why she joined their campaign in Washington, D.C., despite her opinion that voting was meaningless. The suffrage demonstrations, which were viewed by many as unpatriotic in wartime, made her a political prisoner, too, in solidarity with the men who opposed the draft. Dorothy’s arrests and jailings expanded her life experiences, which, she hoped, would enhance her ability to write about injustices and the costs of attempting to end them. This was material for freelance writing projects while she was unemployed.

“Dorothy understood that war resisters were political prisoners, whereas most average Americans considered resisters to be unpatriotic, even traitorous.”

I’d like to add a postscript. Reading the Bible was important to her back then, as was belief in God, even after she stopped attending church as an adolescent. Was her opposition to World War I completely rooted in secular radicalism? I don’t know. But her disappointment with Christians’ failure to live Jesus’s law of love does not eliminate the possibility that deep down, her opposition to war, while not disavowing all forms of violence, imperfectly honored Jesus’s radical message that Christians must care for one another. Fighting wars and engaging in violence was not what Jesus had in mind in proclaiming the “good news.”

C.Z.:

Dorothy’s attraction to the poor and immigrants brought her into the Catholic Church. She could not have credited its position on matters of war and peace.

A.K.:

That’s right. She loved the poor, wanted to be with them. In addition to the Bible, the socially conscious fiction that she loved from childhood nourished her identification with, compassion for, and activism on behalf of the poor. And her engagement with the poor as a radical journalist certainly intensified her commitment to work for significant social change on their behalf. It was never her aim to hobnob with bishops or with other “worthies.”

When she converted, American Catholics of the 1920s were struggling to establish themselves as loyal Americans, capable of maintaining their faith while participating in American institutions, society, and culture, as individuals, not as an ethnic religious bloc. Catholics were instructed to obey authority. The message of “pray, pay, and obey” applied to the government as well as the Church. Remember the long history of anti-Catholicism and nativism in the United States. The Ku Klux Klan was resurgent during the twenties, and even non-members shared many of its views about who was responsible for the alleged moral decline of the United States. Among its targets were immigrants, Catholics, Jews, Blacks, and urban dwellers. At this time Congress passed two draconian immigration laws aimed at drastically cutting immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe, the homeland of the alleged dregs of society, mainly, poor Catholics and Jews. These were the people Dorothy loved!

Catholic reformers, like the influential Rev. John A. Ryan, saw war as an opportunity for social reconstruction that could curtail injustice, ultimately eliminating some of the causes of unrest and war. He and others were involved in forming the Catholic Association for International Peace (CAIP) during the late twenties, roughly at the time that Dorothy joined the Church. It did not contribute to her conversion. She eventually learned about the organization, but CAIP adhered to just war teaching, which allowed for Catholic participation in those wars that met certain criteria. Dorothy would root her pacifism in the Gospel: love for God and neighbor. In practice, CAIP consistently deferred to U.S. authority in time of war. The organization finally collapsed under the weight of the moral issues raised by U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War.

At the time of her conversion, she probably hadn’t yet entirely worked out her own views on war and her pacifism would develop incrementally once the Catholic Worker was underway.

C.Z.:

Like so much else, Dorothy’s pacifism seemed to widen and deepen over time.

A.K.:

I agree. The seedbed of her pacifism extended back into her Protestant young adulthood. Her familiarity with the Bible remained a significant part of her spirituality and informed her pacifism. Back then, the Catholic laity was discouraged from Bible reading. It would take a convert like Dorothy to advance biblical nonviolence as an essential Catholic teaching. She placed enormous emphasis on the commandment to love God and love neighbor. She understood it as the core teaching of Jesus and pondered over it from adolescence until her death.

“It would take a convert like Dorothy to advance biblical nonviolence as an essential Catholic teaching.”

Her pacifism, opposition to war, or more accurately, her resistance to war, her noncooperation with it developed as she thought through the implications of love of neighbor at the Catholic Worker.

Being a Catholic pacifist during the early thirties was not as controversial as it would become later. Why not? At the time, there was widespread revulsion against war in the United States and Europe. Many Americans questioned whether, with the global depression and the rise of fascism, World War I had truly made the world “safe for democracy.” The cost in lives and dollars was troubling. And in those economically desperate years, war profiteering seemed particularly offensive. The robust isolationist movement, although in some sense a rejection of engagement in the world, provided cover for pacifism during the early thirties. But it did not define pacifism. Both stood against war—and the United States was not then involved in a full-scale conflict. What was then taking place south of the border wasn’t of much concern to citizens. Pacifism becomes more publicly controversial when a country openly plans for or goes to war. Additionally, Dorothy remained influenced by the leftist critique of war but not necessarily by the Left’s approach to addressing social, economic, and political injustice. She saw the truth in its insights, for example, in the exploitation of workers and the colonized, and she determined that the critique was valid.

The basis for her pacifism in the thirties and beyond was Jesus’s law of love. Unconditional love. How can you kill someone while unconditionally loving them? You cannot. And Dorothy was already living that unconditional love among the poor and the injured at the Catholic Worker. If ever there was a seamless garment approach to human dignity and the survival of humanity, this was it!

Dorothy’s pacifism during the Spanish Civil War launched the first indication that her pacifism would be controversial and alienate some supporters. Many of the Catholic bishops sided with Franco because he pledged to protect priests, sisters, and Church property. Her bold refusal to support the use of violence on either side was at odds with their position. Consequently, she was criticized by Catholics for not supporting Franco and by the Left for not supporting the anti-fascist Loyalists. Her stand cost the donation-dependent Catholic Worker vital support.

C.Z.:

If ever I could choose an event in Catholic Worker history where I could be that fly on the wall, it would be the retreat in 1940, sparked by Dorothy’s assertion, proclaimed in a banner headline, that the movement would remain pacifist.

A.K.:

Oh my, yes! The sparks must have been flying. Even during the thirties, two strands of pacifism coexisted, somewhat uneasily, I suppose, at the Catholic Worker. Dorothy advocated gospel pacifism. Some, for example, Bill Callahan, who did champion the right to conscientious objection, preferred just war pacifism. And still others concluded that World War II was a just war. Dorothy’s gospel pacifism meant absolute opposition to war. Just war criteria could lead to a pacifist conclusion if one insisted that a just war in the modern era was impossible, given the indiscriminate injury inflicted on civilians by modern weaponry, for example. But, as in the case of CAIP, it could be interpreted to conclude that the cause was so just, that the enemy was so evil, that all means could be employed to counter the threat. We know that the pacifism of the Catholic Worker resulted in certain C.W. groups ending the distribution of the New York paper. The Chicago group published its own non-pacifist version. Dorothy demanded that the New York paper be distributed. Printing a local one was acceptable, but the New York paper needed to be distributed as well. As for the draft, Dorothy and Joe Zarrella testified in Congress against its passage in 1940, more than a year before Pearl Harbor.

Let’s outline some major wartime issues that Dorothy addressed. Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, she recognized that the United States was involved in an undeclared war. Aid for Britain preceded the formal war declaration. She specifically advocated gospel pacifism, a spiritually grounded practice, even prior to the declaration of war. As a defender of human rights, she had already pointed out Nazi excesses, condemned anti-Semitic falsehoods, and was one of a very few Americans to openly disagree with the incarceration of Japanese Americans in “internment camps” on the West Coast. Since she lived at the subsistence level, on donations and royalties, she would be paying few if any taxes that would support war.

She feared that the paper would be shut down, just as dissenting publications were during World War I. And she recognized that her views could send her to prison as a disloyal person. Indeed, her name appeared in an FBI list of persons who might be detained because of their alleged subversive views. Fortunately, these fears were not realized. Nonetheless, the FBI amassed a hefty file on her views and activities, some of which falsely accused her of being a communist.

When the drafting of women was rumored, she joined with others who would refuse to sign up. This potentially bold move, a large step beyond conscientious objection, meant that she planned to resist cooperating with conscription.

Observing that war industries support the war effort, she believed that such work, remunerative though it was, should be shunned. She objected to the goal of “unconditional surrender,” which hampered negotiations to end fighting. And, of course, she wrote a powerful condemnation of the use of the atom bomb. I could go on!

Ultimately, subscriptions plummeted during the war. And several C.W. houses closed, perhaps as much from the lack of available volunteers, who were drafted or employed in war industries or the conscientious objectors performing alternate service. Some of the Workers voluntarily joined the war effort. Dorothy continued to love them and published their letters from the front.

She tolerated positions at odds with hers within limits. To those who refused to distribute the N.Y. paper because of its pacifist position, she asked them whether they could call themselves Catholic Workers. The pacifist position must be shared even if they introduced positions at odds with it.

I’d like to note the significance of the pacifist writings of Dorothy and others during the war. Where else in the popular Catholic press would readers have found information on conscientious objection, the philosophical and theological basis for pacifism, and what pacifism looks like in practice?

Using the language of Fr. John Hugo, she wrote about employing the weapons of the spirit. By weapons of the spirit, she meant prayer, fasting, the works of mercy, etc., directed at trying to promote peace and justice to end violence. Pacifism, she believed, was not passivism, in which one would simply claim to be against war and do nothing. Before World War II began, she read Richard Gregg’s Power of Nonviolence

, which familiarized her with ways to practice nonviolence.

Dorothy shared the task of writing about war and peace with others, too. For example, she invited two priest scholars, G. Barry O’Toole and John Hugo, to write a series of detailed articles that used traditional just war criteria to make a case for Catholic conscientious objection and opposition to war. She was a journalist, not a philosopher or theologian. Surely the paper presented a strong case for Catholic pacifism to wartime readers and, I would suggest, for posterity.

C.Z.:

In frustration, Dorothy would wonder, “But where are the bands of Catholic conscientious objectors?” Some were at Camp Simon, where Catholic conscientious objectors performed work of “national” consequence. Tell us about Dorothy’s sympathy and support for these men.

A.K.:

Alternate service was expected of those, who for reasons of religiously formed conscience, could not participate in the war effort during World War II. First, it was difficult for Catholic conscientious objectors to be recognized as such by the government. The Catholic Church is not one of the historic peace churches like the Brethren or the Mennonites who honor their members’ pacifism. Most Catholics serving on draft boards hadn’t even encountered just war teaching, much less a Catholic case for absolute pacifism. This was still a time when Catholics emphasized our differences with Protestants. And in the modern era, Christian pacifism was born within Protestantism. Plus highly influential Catholic prelates, like Cardinal Francis Spellman, were ardent supporters of the war.

Some of the Catholic Worker conscientious objectors joined the ambulance corps and performed noncombatant service. Others worked crushingly long hours under the most difficult conditions in hospitals and mental institutions. And then there were those segregated from society at Camp Simon, like Gordon Zahn who spent three years there as a young conscientious objector and later became a pioneering Catholic thinker and writer on nonviolence. The men were not paid for performing what was, in fact, utterly inconsequential work, mostly chopping and bundling wood to keep themselves warm, clearing debris from an earlier hurricane, and cutting down overgrown tree limbs. They were basically left to fend for themselves in this former Civilian Conservation Corp (CCC) camp; neither their government nor their Church wanted anything to do with them. Conditions were dire. The men suffered from boredom, isolation, and insufficient food and housing. Better run camps sponsored by the traditional peace churches tried to provide help, and though funds were scarce, Dorothy’s and the Catholic Worker’s efforts at aid were crucial. Dorothy made certain that The Catholic Worker

published articles written by and about the men—that their situation would be known and perhaps encourage additional support. This was extraordinary. Previous American Catholic conscientious objectors, so few in number, had never had this level of recognition. But the camp closed before the war’s end. It just wasn’t sustainable.

‘Salt,’ a newsletter published by men in the Catholic conscientious objectors camp that the Catholic Worker struggled to help support.

C.Z.:

The Catholic peace movement of the 1950s stressed noncooperation—personified by Dorothy’s annual refusal to take cover during the mandatory air-raid drills. That emphasis on noncooperation also characterized the actions of the Berrigan brothers and the draft card burning during the Vietnam War. While the mainstream press gave major coverage to these latter actions,

The Catholic Worker

surprisingly carried very little. Can you explain why?

A.K.:

Noncooperation represented Dorothy’s personal approach to a Christian response to World War II and beyond. She knew the costs of prison, based on her World War I experience and those of friends who had defied the draft. The stakes for noncooperation with the air-raid drills involved possible jail time, and she was arrested a few times. As an opponent of war, the arms race, and weapons of mass destruction, she was paying the “cost of discipleship” by putting her body on the line. She set a demanding example.

“As an opponent of war, the arms race, and weapons of mass destruction, she was paying the ‘cost of discipleship’ by putting her body on the line.”

Most of the public supported the Vietnam War for several years. Catholic Worker activists were among the earliest protesters against U.S. intervention in Vietnam. Starting small, the antiwar protests took many forms—picketing, marching, draft card burning, signing complicity statements, liturgies, and large gatherings. With its focus on issues like inequality, war, and free speech, the decade of the sixties itself was an era of wide-ranging protests and uprisings. In 1965, Dorothy supported individuals publicly burning their draft cards, a contentious issue. The men were called draft dodgers, communists, and worse. The destruction of draft cards had recently been criminalized and supporters of the war would engage in counter-protests at these events. At one such event, they called Dorothy “Moscow Mary,” and some urged the draft resisters to “burn yourselves.”

In the fall of 1965, the self-immolation of a Catholic Worker volunteer, Roger LaPorte, caught pacifists, including Dorothy and Catholic Workers, off guard. Church authorities seemed to blame pacifists. Having kept his plan to himself, LaPorte’s action and death shocked everyone. Considerable soul-searching took place at the Catholic Worker, as well as among supporters of nonviolent protest, those within the U.S. Catholic Church, and others within the general public. Had anyone at the Catholic Worker known, they would have stopped him. Still the Catholic Worker was being blamed by some for his death. It was a time of great suffering for Dorothy.

Some of the Catholic Workers who had burned their own draft cards were imprisoned. And some of the imprisoned “did hard time,” which created serious problems for themselves and their families. Imprisonment is emotionally, physically, and spiritually challenging. Dorothy felt that sometimes young people were inadequately prepared for prison. She supported resisters, but she wasn’t one to pressure others to risk imprisonment.

The Catonsville Nine draft board raid in 1968 was an action that Dorothy could not have anticipated. Mixed feelings about it surfaced at the Catholic Worker. Brothers Daniel and Philip Berrigan were nourished by C.W. pacifism. After engaging in a variety of protests and in founding several peace organizations, they decided to take public protest to a different, much higher level of risk. Dorothy appreciated their spiritual depth. She never wavered in her personal support for Dan and Phil. At their federal trial, she spoke in support of the raid. Writing about them, she focused on their sacrifice as well as their prayer and fasting. It was a prophetic stand by priests in a Church that failed to advance a robust critique of the war or renounce its cozy relationship with the U.S. government. It was as though the American Church had already forgotten “Pacem in Terris” and Vatican II. But she expressed concern about young recruits in such raids and offered alternative nonviolent options. Naturally, she hoped that none would cross the line into violence against humans. The costly trial and the Berrigans’ decision to go underground, both breaking with traditional Gandhian nonviolence, were areas of disagreement that arose after the trial and with the continuation of draft board raids by others through the early 1970s. Mostly, she kept her reservations private, lest she further fracture the Catholic peace movement. She could be judgmental, as she readily admitted, but she usually preferred to criticize privately. The volatility of American society was still another consideration.

C.Z.:

Can you reflect more on the character of Dorothy’s pacifism? At times it seems to carry a kind of penitential tone.

A.K.:

For me, a penitential tone does not dominate Dorothy’s pacifism. I love how her pacifism responds to the signs of the time. She was so well informed about the horrors that the government has committed in our name. Dorothy was deeply disturbed by the sins of all sorts of violence—loss of human life, abuse, the deliberate denial or destruction of what humans need to survive in decency. Few can match her record in providing immediate help, charity, to those in need, combined with working toward that world in which it is easier for people to be good and just. We Catholics are probably more disposed toward charity than toward justice. Her example reminds us of the need to aim for both.

As a personalist, she felt the need to acknowledge and challenge what has taken place in the past in our name and to be prepared to address what is occurring in the present, and what is likely to take place in the future. And remarkably, as a Catholic prior to Vatican II, she was open to working with non-Catholics who shared her concerns.

C.Z.:

Though there has always been a peace tradition running through the larger Catholic tradition, is it fair to say that that tradition was largely lost to the American Church? And that Dorothy Day through the Catholic Worker movement she founded with Peter Maurin played a major role in its revival? Perhaps that alone should make her a saint!

A.K.:

Dorothy retrieved the Catholic peace tradition as best she could in the pages of the paper, whether it be quotations, illustrations, or reporting on the peace activities of the Catholic Worker and others. Even if Dorothy hadn’t written a word, Ade Bethune’s depictions of St. John Gualbert, St. Martin, and Jesus riding on a donkey conveyed the message of peace, forgiveness, and Jesus’s instructions for a world anchored in justice and peace. Dorothy referenced the Sermon on the Mount as the source of Catholic Worker pacifism. Could there be a more powerful claim than that? She was not a trained scripture scholar, but she faithfully grasped the radical implications of Jesus’s words and example. I think of her love for Pope John XXIII and his encyclical, “Pacem in Terris,” was a major step in the Church redefining its role in the world and its relationship to governments, nations, and peoples. And I recall her praying, fasting, and visiting bishops during Vatican II in the hope of gaining support for conscientious objection and a condemnation of indiscriminate bombing. Where would we U.S. Catholics be without the sound foundation for Catholic pacifism prepared by Dorothy and others whose writings she solicited for the paper?

C.Z.:

Anything you’d like to add, Anne?

A.K.:

I wish to thank you, Carolyn and the Guild, for providing this opportunity for me to share my thoughts. Everyone should keep in mind that the United States and the Catholic Church of Dorothy’s lifetime were not the same as they are today. Dorothy’s many accomplishments, including her gospel pacifism, began in an American Catholic culture that valued its conventional patriotism, not its pacifism. To some, her ideas sounded like communism. But when you read her works carefully, you find that she was offering a radical Christian alternative to communism and capitalism as we know them. It is an alternative grounded in the unconditional love that Jesus shared: a gift that all too often we fail to acknowledge, to accept for ourselves, and to share with others.

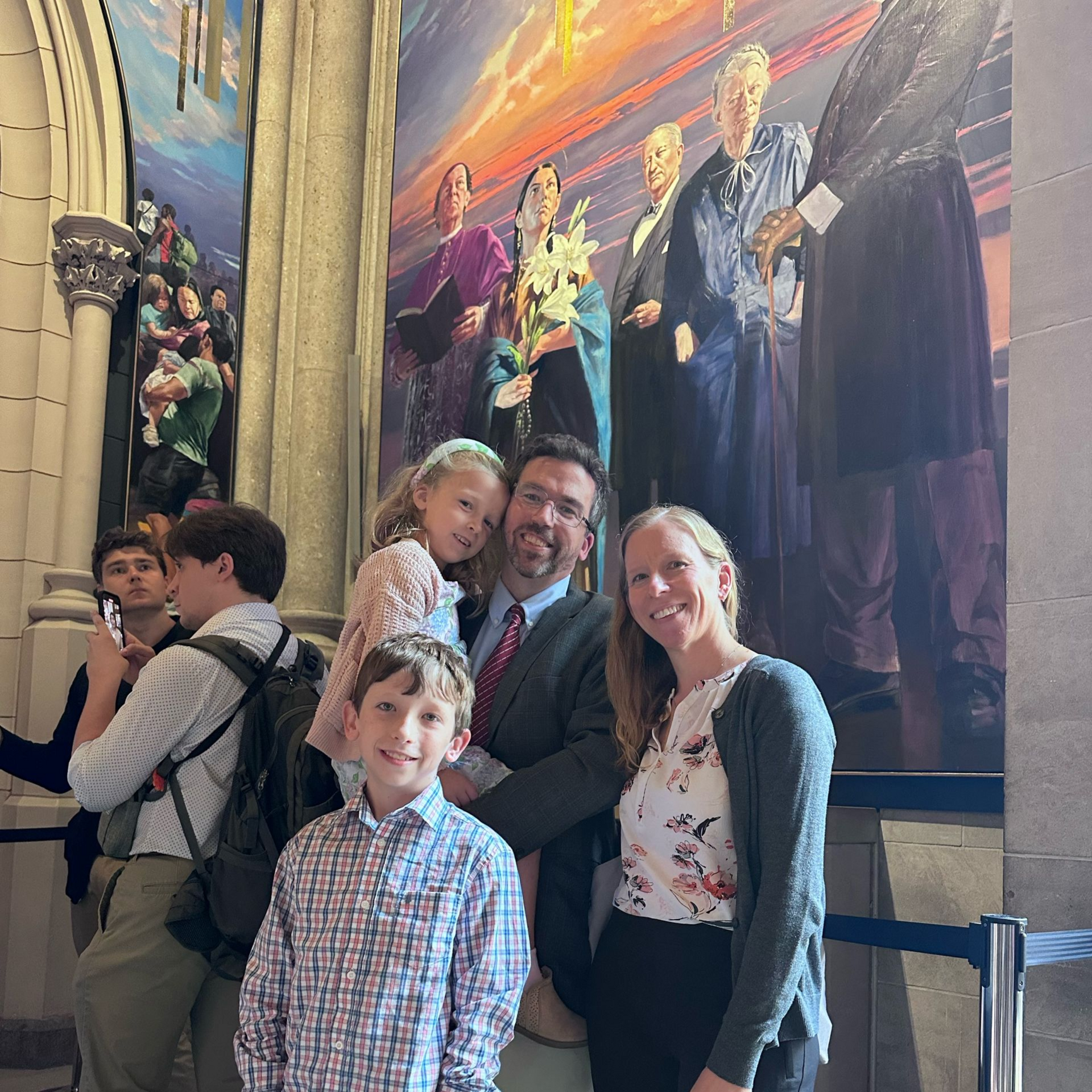

Dorothy Day, at civil defense drill protest (in front of Ammon Hennecy, who is carrying picket sign), New York, NY, ca. 1960, Photo by Mottke Weissman

-

Our deep thanks to

Bro. Martin Erspamer, OSB, for the use of his iconic images (preceding columns for “Good Talk,” “Breaking Bread,” “Sowing Seeds,” “Signs of Holiness”)

-