PHONE

555-555-5555

ADDRESS

Dorothy Day Guild

1011 First Avenue, Room 787

New York, NY 10022

SAVED BY BEAUTY, Artists of Hope

Bro. Martin Erspamer, OSB and Bro. Michael (Mickey) McGrath, OSFS are both liturgical artists, widely recognized for their creative work. Meeting in the pages of the Guild’s newsletter, they bring an artistry and open-heartedness long associated with Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker.

From its very beginning, the Catholic Worker has been blessed by grace-filled encounters, their number suggesting more providence than coincidence. How else can the meeting between Peter Maurin and Dorothy Day be understood? He lit the match that set the new convert on fire to see what the Gospel, if lived, would look like, a match that led to a movement and even to a cause for canonization. Both still kindle our imagination with the possibility of new life, new hope.

Beauty is an entryway to our imagination. Even as a young girl, Dorothy found deep inspiration and joy in literature, nature, and music. She must have felt a kindred spirit when she met nineteen-year-old art student, Ade Bethune, in 1933. Ade had come to the Catholic Worker on East Fifteenth Street. While she was moved by the hospitality offered to the poor, she felt the fledgling Catholic Worker newspaper wasn’t sufficiently conveying the spirit behind the work. She offered her artwork. To this day, her bold images continue to animate the paper.

When the Guild was contemplating the launch of the digital version of its newsletter,

In Our Time, we knew we needed some “Ades” of our own to help us. We found them and they found us: Bro. Martin Erspamer, OSB, and Bro. Michael (Mickey) McGrath, OSFS. Bro. Martin is a Benedictine brother while Bro. Mickey is an oblate of the Order of St. Francis de Sales. Each is an accomplished artist in his own way. Like Ade before them, both are liturgical artists who share a vocation to create beauty that sparks our imagination, bringing people closer to God and to one another.

I first met Bro. Martin through an illustration of his on the jacket of a book about the parables. Despite the proverbial warning, I confess I did get it because of its cover. I just couldn’t resist Martin’s earnest yet girlish sower: long-haired, open-eyed, and forward-stretching in spite of—or maybe because of—her pointed, mismatched slippers.

She quickly led me to other images of Bro. Martin’s, whose artistic work extends much beyond book jackets. Known to work on as many as fifteen diverse projects at a time, his art includes illustrating missals, carving tiles, firing clay pots and bowls, painting stained-glass windows, designing blueprints for churches and houses of prayer, and making liturgical furniture. Each day, he moves between art spaces around the sprawling 250-acre campus of Saint Meinrad Archabbey, located sixty-five miles west of Louisville in southern Indiana.

It was here at St. Meinrad’s where Bro. Martin’s religious vocation came to full bloom, a vocation intertwined with the making of art. He’d always been drawn to art; even as a child, he’d “pick up junk and draw on it.” Later he would study art at Boston University before entering the Marianist order and becoming a brother. For thirty years, he continued to work as a brother-artist in what he felt to be a spiritually satisfying atmosphere.

But it was a commissioned project by St. Meinrad’s that led him to his eventual embrace of the monastic life in 2005. As Bro. Martin shares, “I worked on the renovation of the church, and the Benedictines worked on the renovation of me.” Today, Bro. Martin says he is still a work in progress, Dorothy’s own frequent self-assessment. In fact, Saint Meinrad’s was a favorite place of Dorothy’s. She often visited the Archabbey when she stayed in nearby Tell City with Joe and Alice Zarrella, two stalwart Catholic Workers going back to its early New York days. Joe had the unenviable position of serving as the CW bookkeeper. And it was often Alice’s dollar bill, posted from Tell City and faithfully sent every pay day, Depression be damned, that was the only thing he had to book.

“Artists like Brothers Martin and Mickey enable us to see the life around us with fresh eyes.”

I was reminded of Catholic Worker generosity when Bro. Martin offered his own, opening wide the door to his artwork for us. Besides his endearing sower, which serves as the icon for the new “Sowing Seeds” column highlighting Catholic Worker communities, this newsletter is home to three other images, used as icons for “Good Talk,” “Breaking Bread,” and “Signs of Holiness.”

It was the hospitality of another faithful Catholic Worker couple, Pat and Kathleen Jordan, that brought me to Bro. Mickey McGrath. Nearly two decades ago, my husband and I arrived for a festive Sunday brunch at the Jordan home in Rosebank, Staten Island, just blocks away from where Dorothy had once labored over her typewriter, perched at her kitchen table, to produce the very first edition of

The Catholic Worker.

Mickey’s energy suffused all our conversations. At the time, he was completing a children’s book on Dorothy Day and spoke with the exuberance and delight of a child at play, alive to all around him.

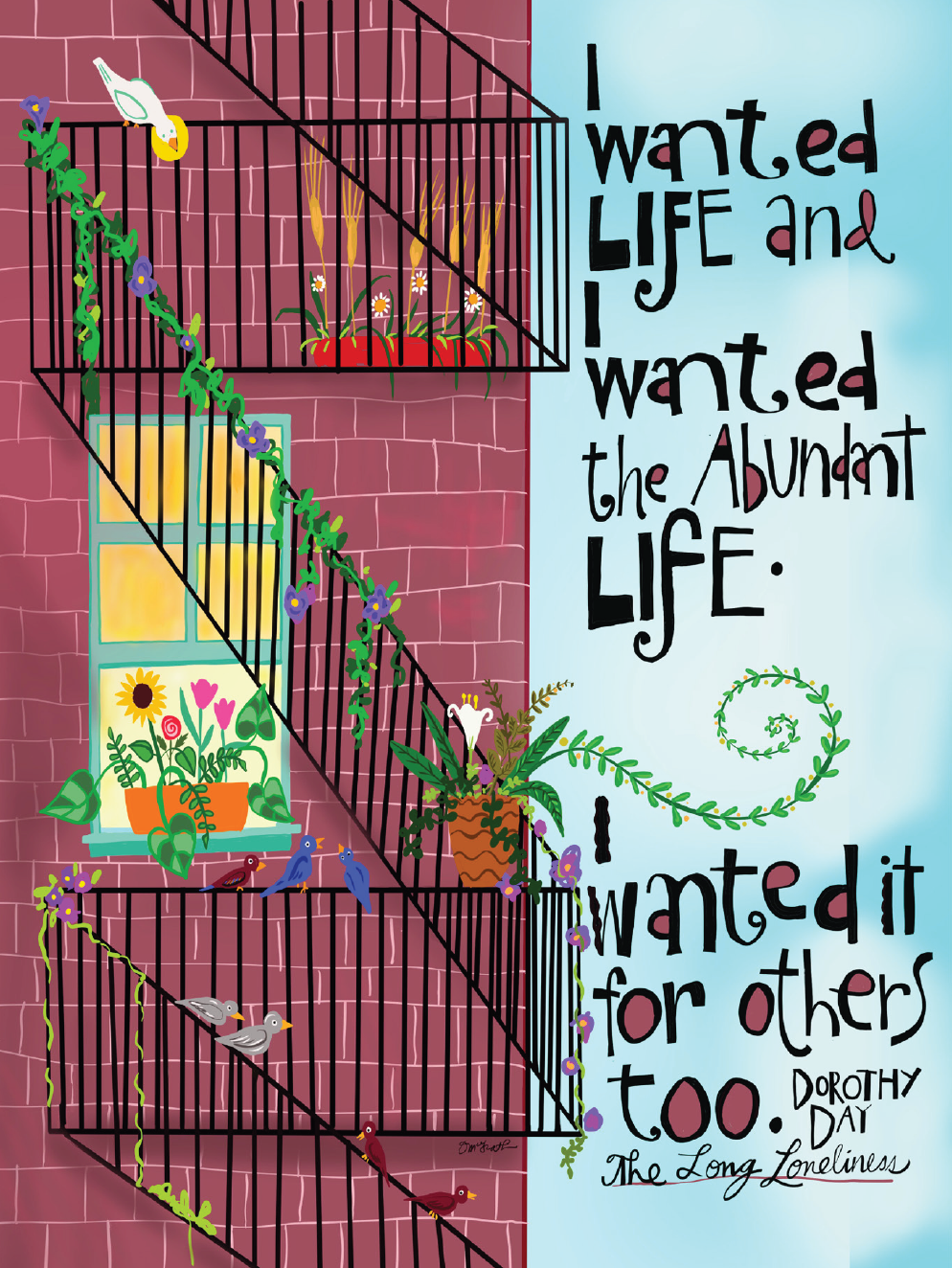

Mickey’s joy stayed with me. So, when the Guild was looking for art to celebrate the historic send-off of 137 archival boxes of evidence attesting to Day’s holiness, gathered over years and weighing easily two tons, he came immediately to mind. Recognizing Dorothy’s passion as a young idealist, a passion that never left her, Mickey created this image below. Since then, we’ve been gifted with other pieces of his vibrant works, including the image for this season’s newsletter,

Love and Beauty Will Embrace, Justice and Peace Will Kiss.

Like Bro. Martin, Bro. Mickey started drawing early. Even as a little four-year-old, safely ensconced under his mother’s ironing board, he would make picture after picture on the backs of discarded papers brought home from his father’s office in an accounting firm.

His first formal lessons were on the weekends during high school at the Moore College of Art in downtown Philadelphia, his hometown. Later, he would major in Art at Moravian College. Drawn to the spirituality of St. Francis de Sales, who was known for his confidence and hope in God’s love, he became an Oblate. As a member of the community, his artistry continued to develop. He earned an MFA in Painting from the American University in Washington, DC, and taught art for eleven years at De Sales University in Center Valley, Pennsylvania.

Today, he works full time as an artist who leads retreats, writes books, and gives presentations. As he shares: “I paint, write, and tell stories—and then travel all over the place telling the stories behind what I paint and write.”

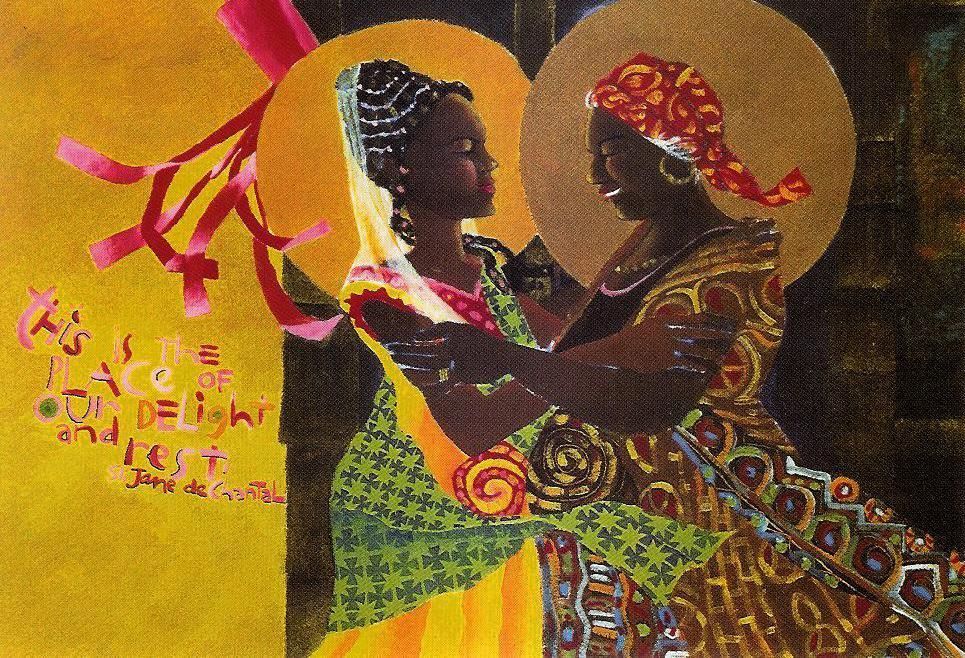

One such story is about his first commission. During a sabbatical from teaching in 1994, he stayed with the Visitation Sisters of Minneapolis, who had recently moved into a poor neighborhood in north Minneapolis. Dubbed, “the nuns in the hood,” they would hang a colorful windsock (a long textile tube designed for indicating wind direction and speed), outside their house on days when they offered after-school activities for local children. Inside the house, above an old mantle, there incongruously hung a colorized print of the Visitation of Mary and Elizabeth by the German Renaissance artist, Albrecht Durer, complete with blonde-haired women with rosy cheeks.

This image became a catalyst for something new as the nuns urged him to create a painting that reflects the women of the neighborhood. What came forth was the

Windsock Visitation. To this day the children of the neighborhood can look upon the meeting of Mary and Elizabeth with a wonder and recognition that had once eluded them.

Artists like Brothers Martin and Mickey enable us to see the life around us with fresh eyes. They open us to experience the promise of a youthful sower and the loving encounter of two dear friends. They call to memory how Dorothy loved to quote from St. Augustine, “All beauty is a revelation of God.” And how she found beauty in uncommon places, even in community among the poorest of the poor.

We are ever grateful to them for the beauty they graciously bring to

In Our Time, helping us to share the grace of Dorothy’s life with others—a life, like beauty itself, that points to God.

Carolyn Zablotny is the founding editor of the Guild’s newsletter, In Our Time, and a longtime friend of the Catholic Worker. A collection of Bro. Martin’s work, The Work of Our Hands: The Art of Martin Erspamer, O.S.B., is available through the Saint Meinrad Books and Gifts Shop. Bro. Mickey’s latest book is Madonnas of Color. Learn more about his artwork at bromickeymcgrath.com. Our thanks to the unknown artist for the use of their illustration as the icon for “Saved by Beauty.”

A Woman of Conscience, a Saint for Our Time

The Dorothy Day Guild supports and advances the cause for canonization of Dorothy Day, initiated by the Archdiocese of New York as a saint by the Roman Catholic Church, and promotes, for the benefit of all people interested in social justice, awareness of Dorothy Day, her writings, the Catholic Worker Movement she co-founded, and her life and witness to the Gospel.

QUICK LINKS

© 2023 All Rights Reserved | Dorothy Day Guild | This site is powered by Neon One